The Maureen Duke Educational Award. Manila Bound.

I left London Heathrow Airport in early March at 10pm. London was locked in

a chilling, sleet-ridden darkness. Heathrow being almost devoid of passengers

with those who had braved the time and weather huddled in small, quiet groups.

Wrapped in dark, generous winter clothing, looking for the entire world like

slow moving standing stones.

Landing at Ninoy Aquino International Airport

some 14 hours later (8pm local time), the heat of the day that had been

absorbed in the fabric of the pavement and buildings radiated into the still

night air. And as a foretaste of Manila, Ninoy Aquino was a pageant, a circus

of colour and noise. The 30-minute taxi journey to my digs offered further

glimpses into Metro Manila. Huge advertising hoardings hemming in the multi

lane express ways. Construction sites vying with apartment blocks and shopping

malls to snag the sky. People, people everywhere, eating, working and living. Occupying

every available space.

Construction sites vying with apartment blocks and shopping malls to

snag the sky.

After a day to acclimatise and with a bag

slung over my shoulder containing my tool kit and umbrella I walked the short

distance from my digs to the Ortigas Building. Even first thing in the morning

the reflected glare from the sun warranted the use of sunglasses. It was then I

noticed that much of the usual street furniture, street signs, advertising

hoardings, graffiti and traffic signage etc appeared bleached out and after

only a few minutes away from my air conditioned building, the humidity and heat

became alto apparent.

My arrival at the Ortigas Building was met

with little, if any fanfare. After negotiating the metal detector and

successfully explaining to the security guards what I was doing with numerous

sharp metal objects I was shown to the lift, given a demonstration of which

button to press (second floor) and left to it.

The doors slid open into a functional, marble

and wood clad reception area. The receptionist, who I quickly learnt was called

Peter, explained that the conservation team had yet to arrive. In my desire not

to be late I had arrived early. I was ushered to a comfortable chair in the

library to wait, having left my bag with Peter (for security reasons). This gave

me an ideal chance to see some of the collection.

The Ortigas Foundation Library (OFL) has a web site (www.ortigasfoundationlibrary.com.ph)

Containing much information, however, briefly, the OFL is composed around the

collection of the libraries founder Attorney (Lawyer) Rafael Ortigas Jr and the

collections of Jock Netzorg and Professor Gregorio F. Zaide. The OFL houses

nearly 21,000 Philippine-related books from the 17th century to the present

day. In addition to antiquarian and rare books, the OFL collection also

includes17th to 20th century publications, rare maps, botanical prints and

objects. The library also houses over 3000 photographs, prints, postcards,

stereo views and illustrated material dating from the 1860’s to after the 2nd

world war. Subjects include early views of Manila along with other cities and

towns, the countryside, architecture, anthological studies, transportation,

landscapes, trade, events etc.

|

The Reception area and Peter from the stairwell. I

soon learnt that the 2nd floor

was in fact the first floor and it was quicker to take

the stairs.

|

The meeting area of the

library set the tone. Informative, yet relaxed

|

The reading room. Much

of the OFL collection is accessible via computer. Recent and more robust acquisitions are

available for research.

|

The core of the collection

is housed in a controlled environment within the public area. Tinted glass

allows for viewing whilst offering UV and sticky fingers Protection

The conservation area consists of two rooms, one for wet

work and one for dry work.

|

The conservation team in the wet room. L to R; Loreto D. Apilado,

Mariano T. Alcantara, Olivia C. Ongoco and Mildred O.

Apilado.

|

The dry room. It would appear that the problem of

never having enough

Space is world wide.

|

Keeping the previous paragraph in mind, it is widely accepted that ideal conditions to store books and related materials are as follows;

Books should be stored away from direct sunlight, which can bleach spines and paper and can lead to an increase in the acid content of paper.

It is important to have constant temperature and humidity within the book storage area with circulation of air. If the room is too hot and dry, leather bindings can dry out and crack; books should therefore be kept as far away as possible from heat sources such as radiators and fires. However, a low temperature in itself does not hamper the growth of mould. It is important therefore to avoid storing books in damp conditions to prevent spores of fungi (mould and mildew), which are always present in the atmosphere, from blooming on books, papers etc. Wherever possible try and keep the room temperature within the range of 16°C to 19°C (60-66°F); with relative humidity within the range of 45% to 60%.

It is easy to understand that the Philippine climate is not ideal for the long term preservation of books and paper. It is not only the environment that conspires against the book. Neglect and over zealous use of self-adhesive pressure tapes such as Selotape used by well meaning people also add to the mix. However, the conservation team have and continue to not only conserve the expanding collection but also take in outside work. The work is diverse, from the manual cleaning of printed material to the restoration of books. The only work that is not carried out in-house is the finishing (titling etc) though at the time of my stay plans were being made to acquire simple finishing equipment.

Ortigas Foundation Library.

Answers to expensive questions.

As with any specialist tools and materials, bookbinding, conservation and restoration equipment can be very expensive. However it is not only the expense that has to be considered. For example, a Leaf Caster can cost more than £5000, plus taxes and shipping. Then there is the space where it will reside, the training of the members of staff, repair and maintenance. Also to be considered is how often will the equipment be used. To be short, no matter how desirable it would be to have a Leaf Caster there may not be the funds and space available.

The OFL answer is simplicity itself. A food blender.

|

| The food blender can be seen on the extreme right of the image with the paper making frames on top of the blue water canisters. |

Using the food blender to make pulp that corresponds with the page or material fiber and tone that requires repairing, single or multiple sheets of paper can then be made. The resulting sheets of paper can either be used wet or dry. The wet paper in-fills can be teased out of the sheet and tweaked into the area that requires in-filling. Basically leaf casting without the leaf caster. The dry paper can then be wet or dry cut as and when required. A very elegant solution.

|

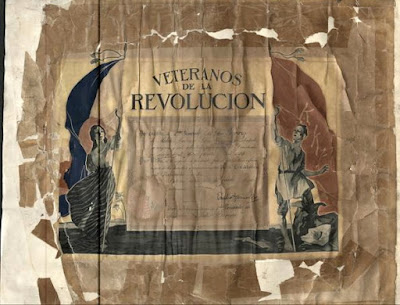

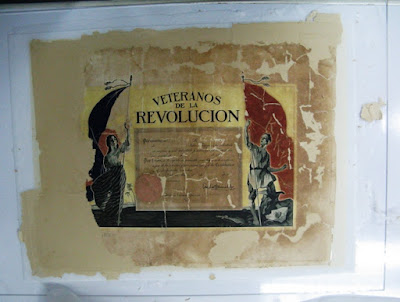

| The original document was backed on to an unsuitable paper. Along with pressure sensitive self adhesive tape there is evidence of insect damage and bleaching. |

|

| Pressure sensitive self adhesive tape is gently removed using a modified soldering iron. Though solvents can be used to remove tape some printing inks can reactivate when solvents are applied. |

|

Because of inconsistencies with the water quality, bottled

water is used. The document is being washed and de-acidified with distilled

water and calcium hydroxide using a hand pressurised garden sprayer. The

document is sandwiched between non-woven polyester sheets.

Even in the controlled controlled environment of the central collection many of the books, maps etc are still encapsulated.

The clear Mylar makes for easy examination of the material inside, thus making

the detection of any insect activity or mould ingress easy. Perhaps in the UK

this form of encapsulation would not be a first choice action. However, it is a

perfect solution when faced with an environment such as Manila, small details

like this, become more and more important and obvious when explained or seen.

Though some bookbinding, restoration and conservation

materials such as basic bookbinders board and some papers are available in the

Philippines much has to be ordered in from abroad. With some orders taking 3

months to arrive forward planning has to be a priority. It is not only the cost

of the materials, as already pointed out there are the additional costs such as

import tax. The conservation teams answer to some of the issues they face have

made me question a lot about how I and perhaps others take so much for granted

and how we could perhaps make better use of what we have.

The specialist materials the equipment used in bookbinding

is either expensive or very difficult to obtain. To this end most of the

bookbinding equipment has been made by Mr Loreto Apilado or fabricated to his

specifications. The various press being made from local wood and materials have

far less chance of warping than imported wooden equipment and are considerable

more cost effective. This idea of using what is local not only applies to major

pieces of bookbinding equipment but also the simplest and perhaps most used

tool. The Folder.

The Final Few Days.

One very important aspect I soon grasped when I was doing my

initial research about bookbinding, restoration and conservation in the

Philippines was the lack of learning opportunities. To this end it was

suggested that as a skill exchange I could deliver a two day course in case

binding.

The short course was booked out well in advance with

students coming from various arts, crafts, libraries and

bookbinding/restoration and conservation backgrounds. One point that I found

very generous of the OFL was that there was at least one assisted place (free

place) this going to a taxi driver who loved books and wanted to learn how to

make one. This gentleman along with the other students showed so much passion,

skill and very genuine desire to learn. I have to say I was touched.

One very important aspect of my work is teaching bookbinding

and related subjects including restoration and some aspects of conservation. I

consider myself very lucky to be able to teach and over the years I have worked

with some very gifted people from all over the world with ever-increasing

numbers of students coming from S E Asia, the Middle East, South America and

Africa. For many of these students returning to their home countries, they face

the prospect of starting their professional working life with limited equipment

and materials. However, their situation can be far more problematic. Because

there has been, in the last 20 or so years, a gradual decline in commercial

hand binderies with the traditional skills being lost or watered down, these

students often find themselves working in near isolation and in some cases with

no recognised suppliers in their country. But by far the biggest differences

are the climate and resources.

The Maureen Duke Educational Award (MDEA) offered me the

chance to learn and work alongside conservators and bookbinders at the OFL. To

have that all important guiding hand, to gain valuable experience of what the

reality of working with limited equipment, space and facilities is, and to

realise what is and is not important. Perhaps as important is a new, flexible

way of thinking. Since returning to the U.K. I have begun to teach my students

what I learnt, for example; all the students on the beginners modules now have

to learn to cut board with just a straight edge and knife, to use minimum

equipment and economy of materials and space. Little things like using methyl

cellulose because it is easier to store as it requires no refrigeration, will

not break down in humid / hot conditions and does not use a preservative will

be taught to students who will benefit.

In addition to the above changes, from August 2016 all

students who start the beginners modules will make their own folder. As I gain

more practical skills I will encourage my students to make other simple hand

tools, to have a working knowledge of how to make and adapt should the need

arise. I have also instigated work on designing a small nipping press that can

be made from minimal and widely available materials.

I realise that these are all small steps but I hope to be

able to improve and to share more with my students the skills and knowledge

that I gained whilst at the OFL.

In Conclusion.

I conclude with the future. After some discussion with the

OFL Conservation team and Mr John Silva (Executive Director OFL) it was agreed

that if possible a teaching programme be started at the OFL. Also, that if

funding was available through tuition fees and other avenues of funding that I

return to the OFL to give an extended programme of courses in 2017, to continue

what has been started.

I would like to thank

The Maureen Duke Educational Award, Peter, Loreto

D. Apilado,

Mariano T. Alcantara, Olivia C. Ongoco and Mildred O.

Apilado, John Silva and all at the Ortigas Foundation Library for their

generosity, help and warmth.

Thank you, Mark Cockram. June 2016.

No comments:

Post a Comment